A Middle School Cross Country Training Plan for Every Environment

Coaches and parents want middle school cross country training to be fun and to lead to a lifelong love of running. But to do this a coach can’t simply take high school training and water it down. Nor should they expect a sixth grader to demonstrate the same commitment to training expected of a ninth grader.

My goal in this article is three-fold...

- To explain why a conservative approach to a cross country training plan in the middle school years sets athletes up for success in high school.

- I will give you a middle school cross country training schedule pdf you can follow today, including warm-ups, workouts, and post-run strength and mobility training.

- Answer common questions about middle school training that I’ve received from middle school coaches, high school coaches, and parents.

Sound good? Let’s go!

A Quick Story About Long-Term Development for Middle School Cross Country Runners

I’ve coached for over 20 years, with eight of those years at the collegiate level. Six of those years I was the recruiting coordinator and assistant cross country coach at the University of Colorado. During that time, I realized there are special considerations when coaching middle-school runners, and that this is particularly important when training middle-school girls.

My experience recruiting NCAA Division I caliber athletes was that many of the women who had the best collegiate careers weren’t standouts in middle school. Some never ran in middle school, and only started running in high school. In contrast, two NCAA XC champions at CU while I was an assistant coach – Jorge Torres and Dathan Ritzenhein – trained seriously in middle school, and by their freshman year in high school, they were training very hard. Both men went on to make US Olympic Teams.

I want to challenge you to take a long-term view for these young learners and implement training that will allow a 12-year-old sixth grader to be better as a 15-year-old ninth grader, and even better as an 18-year-old senior. We also want them to be able to run fast in their 20s, and we want them to become a life-long runner. Finally, we want to be especially careful not to overtrain middle school girls given the lack of a correlation between middle school success and success in college.

Working Backwards with Mileage

Every coach (and parent) wants athletes to run faster in high school than they did in middle school cross country distances. Likewise, we want senior athletes to run faster than they did as freshmen.

But what should a middle school coach do to set this trajectory in motion?

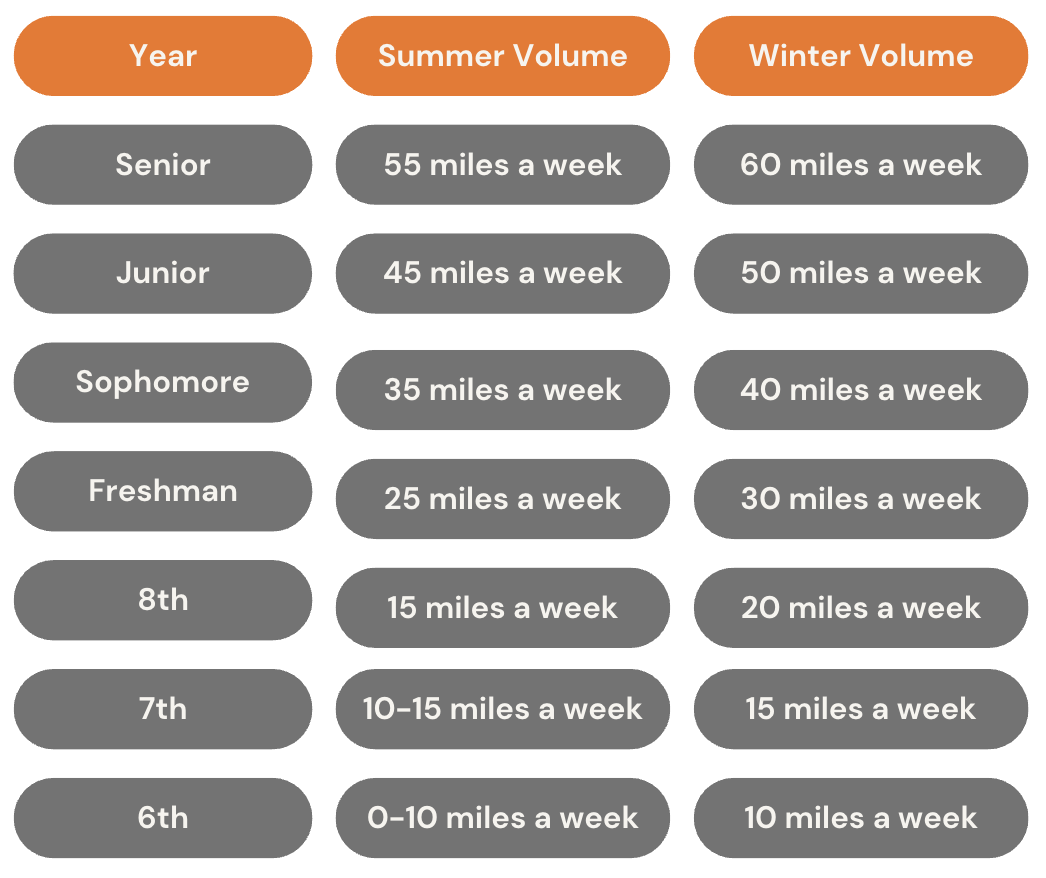

With respect to volume, let’s start at the end – the senior year of high school – and work backwards to a runner’s sixth grade years, with a few underlying principles in mind.

First, I’m not a fan of measuring the volume of training by miles alone. I think it’s nice to track mileage as kids like this practice, but it’s much more important to track: (a) minutes; (b) the volume in meters at race pace; and, (c) the volume of non-running work. All that said, we’ll use mileage at this point in the article so we can all agree on a sound progression of volume over seven years of training.

Second, we’re going to assume that the middle school athlete is a boy and that they aren’t playing other sports. But to be clear, I think middle school athletes should play other sports. And, as the father of daughters, I’d like to see them run less in middle school for the simple fact that there isn’t a strong link between a female runner’s success at age 13 and her success at age 18.

Here’s a simple progression of middle school cross country distances that has the athlete running 60 miles a week the winter before their senior year of track.

Okay, before you say, “Jay - this isn’t near enough. And it’s too simplistic – you just added five miles a season.”

Let’s take it one step at a time and see if you agree with the rationale.

First, the sixth grader does not need to run in the summer to have a blast racing their first season of cross country in the fall.

You, the coach, need to have a plan in place so they can come in with “no prior training” and stay injury-free all fall.

The middle school training plan we’ll discuss includes speed development workouts, playing games like ultimate frisbee, and doing a lot of post-run work (which can be done as games/challenges).

Back in the day, cross country practice consisted of half-hearted static stretching, a run, and two strides to finish the day. That’s nowhere near an ideal practice, for many reasons, the biggest being that there is no work that improves (or maintains) athleticism. We won’t waste time at practice, but as you’ll see below, we can get a lot of training in during a 30-45-60 minute practice without doing a lot of running and while having fun!

Our goal during these years is for kids to have fun racing, while laying the foundation for them to run “real” volume their sophomore through senior years.

Second, we need to think of each calendar year as having four seasons:

- Summer

- Fall - Cross Country

- Winter

- Spring - Outdoor Track

There are some states that have an indoor track season, but to simplify things we’ll focus on outdoor track (though I’m a big proponent of hard-training high school runners getting a chance to run a few indoor races to break up the training).

A high school sophomore who makes 85 percent of summer practices would be at the 35 miles-per-week volume in our progression. But once school starts, they’ll likely have a week or two at 40 miles, as they’re going to attend every practice, and they’re covering more ground on their long runs because they’re running faster (and they may be covering more ground on their easy runs, too).

Here are some questions you might have regarding the progression above...

“I can see how this makes sense, but I still think the volume for middle school kids is low. Will they race well running so little?”

Yes, if they train the right way with the training I’ll share below, they’ll stay injury-free. Injury-free athletes train consistently. Consistent training leads to fast racing.

Now, will your team win the middle school state XC title with this volume? Probably not. They’ll probably get beat. But that’s not our goal, is it?

We didn’t set out to be the middle school state cross country champions.

We set out to create a culture where running is fun, where racing is fun, and where kids get better from the first meet of the year to the last meet of year.

All of this will happen when your kids run 4-5 days a week and have fun at practice.

“I want a senior boy running 70 miles a week the summer before his senior year. So, as a seventh grader doesn’t he need to be running much more.”

Sorry, that’s just not true.

You can have a boy run the exact same volume in middle school as above and then get going with more volume their freshman year of high school.

What you don’t want to do is extinguish a 12-year-old seventh grader’s love for the sport. At that age, they are still 5-6 years from their fastest high school running. And it’s 10 years away from their fastest running as a college runner. Further, if they want to see how fast they can run for any distance from the mile to the marathon as an adult, that’s going to come in their late 20s or early 30s, which is 15-20 years away from their seventh-grade year. Don’t get greedy with mileage with middle school boys – they've got 15 seasons in high school to increase volume before their senior year of track.

“I think you’re doing these kids a disservice by being so cautious with this progression.

In 2023, 26 high school boys broke 9:00 for 3200m at a single meet (Arcadia). If you want to be in the top 50 high school girls in the county in cross country you need to run 17:30s, which means you come through the mile in 5:36 and the two-mile in 11:12.

How are we ever going to get there if they don’t run more in middle school.”

I get it. High school kids are running fast. Really fast.

And...

For every athlete at the levels just described there are multiple athletes who didn’t improve at the same rate in high school as they did in middle school.

You can say they “peaked too early,” they “flamed out,” or were “burned out mentally,” all of which describe runners who failed to run faster as seniors than they did in middle school or early in high school. In contrast, a conservative approach allows a 16 year-old sophomore to train hard once they’re sure they love the sport and want to see how good they can be. An aggressive middle school training plan may mean this athlete, come winter of their sophomore year, isn’t fired up to train.

How about one more question...

“I have a rising eighth-grade boy that wants to go all in on XC. He played soccer in sixth and seventh grade and has been swimming competitively the last two years. But he just finished seventh-grade track and now wants to drop the other sports and be a runner. We start training in mid-June.

If he runs five days a week, won’t he hit more than 15 miles a week? This boy is a good athlete and I feel like I’m doing him a disservice if I put a cap of 3 miles of running a day on him.”

This is the best argument thus far.

Let’s start with the term “disservice.” It’s defined as a “harmful action.” I think I’ve made the case that assigning too much running in middle school without considering athletes’ long-term running careers is a disservice. But I agree with allowing an eighth-grade boy who has done other sports, then falls in love with running, to do more.

The question in this situation is, “More of what?” What should he be doing?

Hint: He doesn’t need a lot of slow jogging.

Hint: He needs to become a better athlete over the weeks and months he’s at practice with you.

I’ll clearly lay out the proper training below, but the simple way to look at it is we’re going to run fast, we’re going to do a lot of work to improve athleticism, and we’re going to improve this athlete's strength and mobility so they can handle more running in high school

...and we’re going to let them run more than the above progression after we have done everything else.

Let’s go back to our progression and what the athlete did prior to joining your team in the summer...

Let’s assume that he was either at track practice or at a middle school track meet five days a week in seventh grade. He ran the 800m and the mile. The coach never assigned a long run, but did assign some long hills that were 60 second long, and he’d do eight of them. With the jog back down the hill that workout was close to 20 minutes of an elevated heart rate. The athlete ran 200s and 400s, but often slower than 800m and 1600m pace (which was a coaching error, but that’s a different topic). The athlete raced well because he had a big “aerobic engine” and was fairly fast from years of playing soccer.

Here’s what we’re going to do in the summer before eighth grade and in the fall cross country season.

The Car Analogy from Consistency Is Key

Let’s use the analogy of a car. The heart and lungs, the circulatory system, and the mitochondria in skeletal muscle make up an athlete’s “aerobic engine.” Every race distance from 800m on up is primarily fueled by the aerobic metabolism (see the table below). A middle school athlete will be racing roughly 3200m most meets, which means that they need a solid aerobic engine.

But this athlete is coming in with a big aerobic engine from all the years of swimming. What’s counterintuitive is that this could mean they have a higher risk of injury because – continuing our car analogy – they have a big aerobic engine, but a weak “chassis.” We’ll consider the bones, muscles, ligaments, tendons and fascia the chassis. In the same way that a fast car with a big engine needs a strong chassis, we’ll need to do chassis strengthening work daily. This is the post-run “strength and mobility” we’ll do, but it will also come in the form of circuit workouts at certain times of the year.

Swimming is great – and the swimming/soccer combo is a great background for middle school runners – but the problem with swimming for our athlete is that his body isn’t used to the pounding that’ll happen when he runs. This isn’t a huge problem, but it is one we need to be mindful of. My college coach would often say to a stellar teammate of mine, who struggled with injuries, “You have a huge engine, but you have a VW beetle chassis.” Our training is going to have a big focus on strengthening the chassis to handle the athlete’s engine, which will keep him injury-free.

Finally, this athlete needs to “rev the engine” most training days by doing strides. And some days we’ll do an entire practice devoted to speed development.

If you’re serious about helping your athletes, make sure to download – for free – the chapters from my book, Consistency Is Key, where I explain the car analogy. It’ll take less than 10 minutes to read and you’ll fully understand these concepts.

Middle School Cross Country Training

What follows is a conservative approach for middle school runners, and one that will lead to both fun times on the team and fast times on the cross country course (and the track) in high school. If you’re looking for exceptions to the rule – for female athletes and male athletes who trained extremely hard in middle school and continued to run well for another decade – you'll find them. But, they’re rare. Our focus is what’s best for the vast majority of kids.

Our first goal is simple: we want the training to be fun!

How do you know it’s fun? Simple.

Do they show up excited to be at practice? And do they leave having had a good time?

We’re going to forego killer workouts and let the races be the most challenging days of the week.

This is one of the biggest mistakes I see middle school coaches make – they want to train too hard during the week.

Going back to the goal of long-term development, we don’t want a middle school runner grinding 1-2 times a week in workouts, and then racing once a week, and possibly twice, because the risk for both injury and burnout goes up dramatically.

But the difference with middle school cross versus high school cross country is that middle school kids can and should race more often. And they’ll race well if you follow the simple workouts below, which improve athleticism yet still help the athletes build stronger aerobic engines.

Now let’s look at the type of athletes who will be joining your program. They’ll either be coming in with a background in other sports or middle school cross country will be their first athletic experience.

Building Better Athletes

When athletes come to you with a background in sports, you need to say to yourself, “How do I ensure they don’t lose any of their athleticism while they’re running cross country?” For the athlete who has never done a sport, we want to improve their coordination, functional strength, and mobility. Simply put, at the end of the cross country season they should “move better” than they did when they first meet you.

To help both types of athletes we’ll do a dynamic warm-up that has them moving in all three planes of motion and post-run work that will both maintain and improve the strength and mobility they brought to cross country.

“This sounds good, but I don’t know what the three planes of motion are.”

When we're coaching cross country, our primary focus is on forward motion. But that's just one part of the picture. Human movement involves three planes of motion.

The sagittal plane is like an invisible wall splitting your body into left and right halves. Movements here are forward and backward. Think of a sprinter in the 100m coming out of the blocks—that's sagittal.

The frontal plane is like a glass sheet dividing your body into front and back halves. Movements here are side to side. Think of a shortstop in baseball darting left or right to catch a ball—that's frontal.

The transverse plane cuts your body into top and bottom halves. Movements here are about rotation. Picture a golfer twisting their torso for a swing—that's transverse.

In cross country, we're mostly dealing with the sagittal plane. Understanding all three planes of motion, however, enhances our coaching in general, and specifically it’s going to help us keep middle school runners injury-free. Remember, we need them to be the best athlete they can possibly be, so the ability to move in all three planes of motion is important.

One more thing while we’re on the subject of planes of motion...

Let's not forget that running has a bit of transverse plane movement. It's not as obvious as the sagittal plane, but there's a subtle rotational action at the hips and shoulders during a run.

Think about it – when the left knee comes up in running, the right hand comes up. So, there is a very subtle rotation of the left hip going just a touch toward the midline of the body, and the right shoulder going just a bit toward the midline. This may be easier to picture if you were a bird watching a runner from above.

Now, you might be asking, "What about the frontal plane?" And that's a great point. Running doesn't involve much side-to-side action, unlike a shortstop darting left or right.

However, just because running isn't a frontal plane movement doesn't make it any less significant in our goal to maintain the athleticism the athlete had when they joined the team. Even though our runners aren't zigzagging during a race, it's vital they maintain their ability to move in the frontal plane. Keeping this versatility not only sustains their athleticism, but also prevents injuries. So, while we want to race faster and faster as the season progresses, let's remember to nurture their broader athletic abilities too.

Middle School Cross Country Training – Dynamic Warm-up for Cross Country

Let's talk about two warm-up activities you should do with middle school runners: leg swings and a dynamic warm-up.

Leg swings are a fantastic set of dynamic movements that work the legs and hips in all three planes of motion. I’ve been using them with athletes for 20+ years because you can do the routine in less than 2 minutes and they’re effective (they also work for middle-aged coaches before their runs or bike rides or weight room workouts 😊). If you’re pressed for time, make sure to get in leg swings to start practice.

Better than leg swings is getting in a full dynamic warm-up. Take the time to watch the following video with Jeff Boelé, who has coached athletes from middle school through professional 1500m runners. This warm-up takes 13 minutes, and it will take a couple of weeks of teaching before the athletes have the warm-up dialed in. This warm-up is a great way to get an athlete’s heart rate up early in the training session, but also a way to engage the frontal and transverse planes. And for the vast majority of middle school runners the warm-up is challenging enough that they’ll “build their engines” in this 13-minute segment.

You may want to take out the “dribbles” for younger athletes in the first few weeks, as they’re challenging, and athletes may get frustrated trying to learn this. To be clear, this warm-up is fantastic, and it’s a great way to ensure kids stay injury free.

Now we’ve got the first part of our four-part training day: the warm-up.

Before we go on, I want to reiterate this fact: for our middle school runner, where the goal is not to build the biggest engine possible, but to improve athleticism, strengthen the chassis, and improve max speed, the running portion of training isn’t the most important training of the day.

So rather than talk about the running at this point, I’m going to talk about the next most important part of our training, which will come at the end of a training session: the chassis strengthening work.

Strengthen the Chassis with Running Specific Strength Training

A car’s chassis is the frame that holds the engine, as well as the other machinery that makes it move. Using a car analogy, the athlete’s bones are the body’s main structure, and the muscles and tendons, as well as the ligaments and fascia, also form part of the “chassis.” Strengthening each of these is crucial to staying injury-free.

If a coach can help an athlete stay injury-free, with the rare missed day or two here and there, the athlete will race fast, and have fun.

Conversely...

An injured athlete who misses practice and doesn’t get to race isn’t going to have fun.

This is why the best coaches keep the concept of “injury-free” training at the forefront of their minds, and make it the primary goal of a six-month training plan.

The next reason to focus on strengthening the chassis isn’t as obvious.

Young athletes will “build their engines” faster than they can strengthen their chassis. My friend, Mike Smith, who coached at Kansas State University and now coaches at West Point, introduced me to this concept when I was coaching at the University of Colorado.

“Metabolic changes occur faster than structural changes,” he explained. And that’s why he had his college athletes do so much work to strengthen all the components of their chassis, work that I had never seen before.

For the middle school runner, who is coming into your program with either no athletic background, or a modest one, their engines can improve dramatically in just a few months. That means they need to spend a significant amount of time strength training, so that both their engines and chassis improve at roughly the same rate. This does not mean they need to go to the weight room, rather they need to follow my progression of post-run strength and mobility routines that start with body weight exercises.

Here’s the deal...

Middle school runners need to do chassis strengthening work every day that they run.

The post-run routines most people are familiar with are the Strength and Mobility – SAM – routines. Those are great, but there are two problems for middle school training.

First, they are organized numerically. You must do Phase 1 before you move on to Phase 2. For a hard-working athlete who isn’t very strong, it may be frustrating to be on Phase 2 when they have teammates on Phase 4. So, I changed the progressions to colors: Red to Orange to Yellow to Green so an athlete who is doing Orange, which is challenging, doesn’t feel like they’re working less hard than the athlete doing Yellow.

Second, these color progressions are simply better than the SAM progressions and are made for middle school and high school athletes.

I want you to have these progressions, as well as have access to all the videos on your phone.

Let’s move on to the final part of the car analogy...

Rev the Engine Most Days by Running Strides

Staying with the car analogy, it’s important that your athletes “rev the engine” most days by doing strides. A stride is simply a quick, short sprint – anywhere between 70m and 150m – that’s faster than a 5k race pace. There are two simple reasons cross country runners must do strides.

- Your runners must practice running faster than race pace to internalize that “challenging but doable” effort so it feels realistic when the gun goes off.

- They must regularly rehearse speeding up – or “changing gears” – if you want them to do the same thing in a race.

One of the biggest mistakes I see middle school coaches make is that they don’t have athletes doing strides on the first day of cross country practice.

We can easily fix that!

Just follow my Progression of Strides for Cross Country - PDF below - which will safely have your athletes running faster than 5k pace in the first weeks of practice. Consistency is key when it comes to strides. So long as athletes show up to most summer training sessions, they’ll be running 800m or even 400m PR pace for short strides when the cross country season starts.

It’s worth saying this once more: you’ve got to assign strides the first day you meet your athletes, and you must make sure you’re safely progressing the intensity of the strides over the course of the summer so that your runners are comfortable running 800m and even 400m PR pace when the season starts.

Improve Speed with Speed Development

“Speed” and “Speed Work” are two of the most problematic terms in distance running. They mean different things to different people.

Let’s be specific with our usage of the term speed. Let’s talk about max speed as the fastest a person can run. For your middle school athletes, they can only run this speed for 20-30 meters. And they’ll need a “run-in” of 20m or so to get to this max speed.

You want to improve max speed in every middle school runner you coach.

This will set them up to be both faster at all distances, from 800m through 5000m. When their max speed improves, their ability to run PR 800m pace or 1600m PR pace while feeling very comfortable improves. And yes, having better max speed is going to improve their kick at the end of races.

If we go back to our commitment to long term athlete development, it’s vital that your athletes do this work in the cross country season.

Athletes, after they trust the recovery between the repetitions, love these workouts. They get to run fast, and they have fun.

In the training plan I’m sharing below, there will be one day a week devoted entirely to speed development.

Improve Running Mechanics with Strides

It’s going to be easier to “clean up” the athletes’ mechanics when they are running 1600m and 800m rhythm than when they are running 3200m XC race pace. We want to get athletes running “up tall” as our main cue (which simply means you tell them to “run up tall” as they run these strides). That’s going to fix a lot of problems from the hips down to the foot.

There are other things some coaches will want to do with an athlete’s upper body. If there is excessive crossing of the arms across the body, that’s a problem. Yet some of those issues are due to an athlete’s lack of coordination, having not yet gained the general strength to run with good posture. So a weak lower body can often cause odd mechanics with the upper body. The post-run work they’ll do after every run isn’t going to fix this in two weeks or two months, but it will fix these things over the course of many months and a year or two.

Remember, almost every athlete you encounter has not developed significant musculoskeletal strength yet.

Let’s make “strengthening the chassis” a huge part of our training, so that when they’re ready to handle more volume (mileage), they can stay injury-free.

The Middle School Cross Country Workouts – Running Circuits

Circuits are a combination of running for short distances followed by strength and mobility exercises. The video playlist I’m sharing, and the running circuit PDF that you can download, assume that the circuit will be done at a track, but you can do it at a grass field or park as well.

I’ve used circuits with every level of athlete from middle schoolers to professional runners (including Brent Vaughn, who did them the first weeks of his training leading up to winning the USATF Cross Country Championships...this is real training!).

We get two benefits from circuits.

First, we strengthen the chassis with strength and mobility exercises. That one’s obvious when you watch the videos.

The other reason isn’t as obvious. When you do a circuit, your heart rate is elevated during both the running portions and the strength exercises, yet the volume of running is low. That’s why we use the circuits early in the year – it allows us to strengthen the chassis and build the engine, but do much less pounding compared to a long run or a fartlek run.

A middle school coach may want to cut the running portions to 200m rather than the 300m that’s in the videos. There is no need to assign a time/pace, but coaches must tell the athletes to be conservative with the pace of the running. However, if the running portions are slower at the end of the workout than they were at the beginning that’s fine – this is another way to teach athletes to run by feel, and “blowing up” the workout isn’t the end of the world.

The problem with circuits is that they are mentally challenging. While a serious high school athlete could do them for 30-40 minutes and get a killer workout, a middle school coach wants to follow the progressions I have written, doing as little as 10-15 minutes for the first workout.

Finally, while I reject the idea that injuries are an unavoidable part of cross country, there will be the occasional outlier who, typically because of a growth spurt, deals with an injury, or simply can’t run the same volume as their teammates. This circuit training is a great option for these athletes.

In the training plan in the XC Training Essentials (XCTE), you'll have a PDF with all the circuit exercises, as well as QR codes that will take you to the videos of the circuits.

The Middle School Cross Country Workouts – Fartlek Runs

Fartlek is a Swedish term that means “speed play” and there is little doubt that fartlek training is a simple and effective way to gain fitness.

A “true” fartlek is a workout where the athlete is oscillating between multiple paces. We’ll simplify things and go back and forth between just two efforts. We’ll have an “on” portion and a “steady” portion. The crux of our fartlek workout is that the “steady” portion is faster than your athlete’s easy run pace.

This is our first workout where the skill of running by feel is crucial. In fact, many runners won’t be able to execute a fartlek workout the right way in their first (or second) attempt. The reason is that learning how fast they should run during the “on” portion and then running a solid steady portion (and not slowing to easy running pace) is challenging.

You are not going to assign paces, but rather you’ll give these guidelines. Tell them...

“Steady is a pace that is faster than your easy run pace. But just a touch faster.

Let’s dial in the steady pace first, and keep the “on” portion very controlled. Today, the “on” portion should be just slightly faster than the steady portion.

So, there isn’t much of a difference between the two, yet make sure both paces are faster than your easy run pace.

Please don’t look at your watch to see what pace you’re running. Just use your watch to time the segments.

This workout is simple conceptually, but it’ll take a few attempts to learn how to dial it in. Again, the key today is to keep the on portion controlled.”

1 min on, 1 min steady fartlek

The first fartlek middle school athletes will do is 1 min on followed by 1 min steady. The chance of this going perfectly the first time is basically zero, and that’s fine! Most kids will run too fast during the on portion, and not fast enough on the steady portion. Again, this is fine! Learning to run by feel takes time – it's a skill, and a skill that they won’t master in the first two months of middle school cross country.

What’s nice about this fartlek is that we’re working with 2-minute segments, so you can assign 3 or 4 or 5 the first workout.

Specifically, we’ll do 3 min easy and 1 min for the cool down. If you assigned three sets – 6 minutes of fartlek – that's a continuous run of 10 minutes. And then they’ll go straight into the post-run work to extend the aerobic stimulus.

In the progression for kids who ran track prior to summer cross country training, they’ll do 8-12 minutes of fartlek. With the 3-minute warm-up and the 1-minute cool down, we’re looking at a total of 12-16 minutes of running for these athletes.

30-90 fartlek

After they’ve done a 1-minute “on” and 1-minute steady fartlek a couple of times, they can do the 30-90 fartlek. Here they’ll run a “fun fast” pace for 30 seconds – faster than they ran for the 1-minute “on” portion in the previous fartlek – and then try to run a similar steady pace for 90 seconds. This is another 2-minute segment, so the math is easy for the coach (and the athlete).

The mistake here is typically that athletes run too fast on the first few 30-second portions, then are unable to continue to run that pace at the end of the workout. The instruction from the coach is “take the first few repetitions really easy and run a pace you know you can run for the entire workout.”

For an athlete doing 10 minutes of fartlek running (five sets), we want them to be conservative on the first two, then run a bit faster for the rest of the workout.

The ideal 30-90 fartlek – and one we’d expect a high school athlete to execute – is running 5k rhythm or faster on the 30 second portions, while keeping the steady portions much faster than easy run pace.

That said, I would rather see athletes run the 30 seconds faster and have slower 90 second portions because the 30-90 fartlek is a bridge to race pace workouts. Plus, we want them to have fun, and if a team full of middle school athletes is running fast for 30 seconds, then running their normal easy run pace for 90 seconds, that’s a great workout.

Middle School Cross Country Training PDFs

Everything you need for the first five weeks of middle school cross country training is in the XC Training Essentials course. You can enroll for FREE!

- Warm-up routine for cross country PDF

- Daily cross country workouts (5 weeks) for kids for whom cross country is their “first athletic activity” 5 weeks PDF

- Daily cross country workouts (5 weeks) for kids who ran track prior to cross country PDF

- Speed development for middle school cross country PDF

- Running circuits for cross country PDF

- Progression of Strides for cross country PDF

- Post-run strength and mobility (Red and Orange) PDF

Finally, you’ll want to get all these videos on your phone, which you can reference at the track or trailhead. Click here to get these videos for free on your computer, then login on these apps to use them on your phone – Apple or Android.

Middle School Cross Country Training Q&A

Coming soon!